By Max Menkenhagen

With the end of the Second World War and the military defeat of fascism in Europe, the central committee now located in Switzerland can finally take back up its role and coordinate and guide the work of its national branches. Next to this internal organizational work, the TVdN engages in humanitarian and propagandistic projects: Hans Welti, Swiss Naturefriend from Zurich and responsible for the management of the Swiss houses, organizes first aid deliveries of blankets and other basic equipment for the Dutch Naturefriends houses, later on for German and Austrian houses as well, financed by donations from Swiss, American, and Swedish Naturefriends[1]. The TVdN further distributes its magazine ‘Naturefriend’ in around 100 detention- and refugee camps, as well as to the section for ‘Intellectual Help’ of the international Red Cross [2]. Resources are distributed responsibly, so that celebrating the 50 years anniversary of the creation of the Naturefriends movement with a ceremony or a commemorative publication is beyond the organizational resources in 1945. Instead, a small celebration is organized by the local young and adult groups from Luzern.

The central committee of the TVdN does not participate in the first post-war-congress of the ‘Socialist Workers’ Sport International’ (Sozialistische Arbeitersport-Internationale SASI) from the 10th to the 13th of October 1945 in Paris. This absence is symptomatic in a two-fold way. First, the delegate has to be replaced due to health problems, but his representation cannot receive a visa, thus, cannot go to Paris. In this sense, the absence is peculiar to the working conditions in the field of internationalism back in the early post-war period. Second, the central committee of the TVdN utters its concerns regarding the unity with the SASI due to differences in their fields of work. This argumentation appears unreasonable, because it were the big national organizations of the Naturefriends in the first republic of Austria and Germany that cofounded the national Workers’ Sport parent organizations (ASKÖ and ZK). Further, the Naturefriends’ main office in Vienna was co-organizer of the Workers’ Sport Olympics of SASI in Frankfurt and Vienna. The argumentation of the TVdN is therefore rather owed to the harsh anti-communist climate of Switzerland and influenced by the rejection of the central committee towards the hosting FSGT[3]. Alltogether, this stands representative of a central problem the Naturefriend movement faces in the post war period: The heterogenous composition of Naturefriends groups proves difficult, when a potential communist ‘infiltration’ was increasingly perceived as threat to the organization. This not only led to spiteful internal disputes and eventually the expulsion of openly communist Naturefriends and whole regional groups, but also to the ‘Worms-decision’, according to which political actions and statements can only be organized or given with the expressed approval from the national leadership (Frišová, 2010).

International meeting of young Naturefriends from Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Netherlands and Belgium, in Rhineland, Germany, (1925) Foto: NFI archives.

The distancing of the Naturefriends from the all-too socialist left came as a surprise and even as disappointment to parts of the organization. Yet, it has to be seen in the historical context. It was necessary precondition for becoming ‘mainstream’ or at least widely public and successful. More passionat discussions about ideological goals and the politicization of the organization would flame up at a later point, when tensions of the cold war rise to their peak in the 80s and 90s. Yet, this stands representative of the general trend that is to determine the future of the Naturefriends: a changing understanding of socialism, and a changing approach of implementing it in the Naturefriends’ work. Increasing focus is put on environmentalism and natural protection, while the identification as part of the socialist family and the fighting workers’ front moves into the background. Again, this should be understood as a general trend, while single members and partners always differed in their politicization as well as in their stance on and even understanding of socialism and communism.

Whether they are socialist, communist, or none of the latter, the Naturefriends remain critical of the capitalist system. “The behavior of our youth is a mix of individual insurgency and constantly ongoing submission to society. […] Massification, alienation from its own nature, and boundless social isolation have a common root: the property- and power-relations within the capitalist system.” (in: Hoffman, Zimmer, 196, p. 117). Out of this understanding, the Naturefriends see their role as developing those skills are neglected by bourgeois education, first and foremost social and artistic abilities. Further, Naturefriends try to educate about societal relationships and the youth’s role in these, in order to prepare the next generation for social activism and societal action. This approach largely remained the same up until today, hereby fostering self-acting, self-confidence, and self-responsibility via non-formal, nature-based education and amateur arts.

With tensions further rising between East and West, the Naturefriends actively engage in the peace movement and easter marches, criticizing the power politics of NATO and the erection of US rocket bases in Berlin and along the Iron Curtain. At the same time, criticism is balanced, with Kurt Vogel stating that “Whoever thinks that only nuclear bombs from the West are dangerous, should stay at home; you do not belong to us.” (ibid, p. 124).

Naturefriends’ activism in the early 60s might not be concerned with day to day politics, but is clearly politically motivated, especially in the form of activism against nuclear energy, for international understanding, and for socialist democracy. As the self-understanding and mission of the Naturefriends movement is strongly intertwined with the people who make up the network at the specific point in time, the focus of activities change towards the end of the 60s.

Manfred Geiss emphasizes the political role of the Naturefriends movement by stating that it should not leave politics to ‘big authorized men’, but rather take up socio-critical political engagement and turn into a real progressive organization. What follows is a range of activities, focused on activism against the war in Algeria, including field trips into Marocco and the liberated parts of Algeria by the German Young Naturefriends. Here, the French Foreign Legion receives special attention for allegedly being a collection of former Nazis, SS soldiers, and concentration camp guards who continue their fight against communism abroad (ibid, p. 135). The Vietnam war is focus of Naturefriends activism as well, including a ‘Help for Vietnam’ program for the reconstruction of northern Vietnam and the area of the provisory revolutionary government.

Further, especially due to preasure from the German Young Naturefriend groups, contacts with the eastern groups and the FDJ is intensified, not only in order to find out how the Western approach of socialism is depicted here, but also to influence youth work in the DDR, even if in reality influence was excerted from and on both sides respectively.

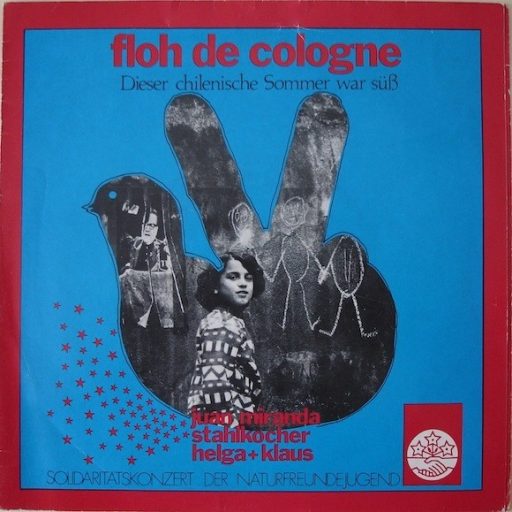

Other highlights include the organization of solidarity concerts for Chile, with German Krautrock-bands Stahlkocher and Floh de Cologne as special guests. Foto: IISG Amsterdam

1970s and Beyond: A Troublesome Road Towards Independent Youth Work

Up until this point, youth work was integral part of the Naturefriends adult organizations. Yet, besides some national member organisations, there was no official and independent youth segment of the Naturefriends on a bigger scale. Now cries for true independence of the youth, not only in single national groups but on an international level, become louder, also due to a difference in interests and understanding of Naturefriends work. While work and management concerning the Naturefriends houses was largely adult territory, the different youth segments focused more on cultural and political work instead. As a consequence, in 1974 the national youth segments agree on the necessity for an international youth organization (NFJI or IYNF).

In order to prepare the creation of an independent, international youth segment of the Naturefriends, a working group is convened in March 1974. Jochen Zimmer, who already was active as first International Youth Secretary of the Naturfreunde Internationale, becomes president of this working group.

Already in June of the same year, the majority of organizations agrees on the general structure of the NFJI (as proposed by Zimmer) and adopts a working program with the focus on improving the involvement of Naturefriends groups in the periphery. Further, a first ‘seminar for environmental protection’ is prepared in the European Youth Centre (EJZ) in Strasbourg, which would turn into a major venue for Naturefriends workshops, seminars and other activities in the years to come.

In January 1975 members of Dutch, Austrian, German and French Naturefriends groups, together with Hans Welti (then Secretary General of NFI) and Jochen Zimmer prepare a draft directive for the establishment of the Naturfreundejugend Internationale (NFJI). Yet, due to disputes over the independence of the NFJI and over the acknowledgement of ‘democratic socialism’ in the directive’s preamble, the executive board of the NFI opposes this draft. After minor changes are made, the President of NFI Werner Schneider as well as Hans Welti approve in March. Yet, independence and preamble are still a matter of dispute, so that the directive is rejected again in May 1975 and another body is created: the special commission for the draft (or guideline) directive.

Still not officially an independent organization, the NFJI’s Presidium meets for its first session in an interim office in Stuttgart, Germany, in late July 1975. Yet, even 2 months later the Presidium of NFI rejects the NFJI directive again. Only a special ad-hoc commission can make a consensus proposal that is approved by the congress. Via this directive, NFJI becomes independent part of the NFI, prone to its statutes. NFI takes over financing guarantee but has in turn the ability to revise NFJI finances. Seat of the NFJI is supposed to be the same as the seat of NFI, but was at that point Stuttgart due to sporadic reasons. Common internal regulations are supposed to handle the relations between NFJI presidium and secretariat and the executive board of NFI. The congress further decides on resolutions that state that the creation of Naturefriends groups in Portugal, Greece, the Nordic countries, and Italy should be supported, and the contact to Eastern European Tourist organizations should be intensified. In addition, the first official Presidium is elected with Wim Bergans, Walter Gscheider, and Rudi Bergmann.

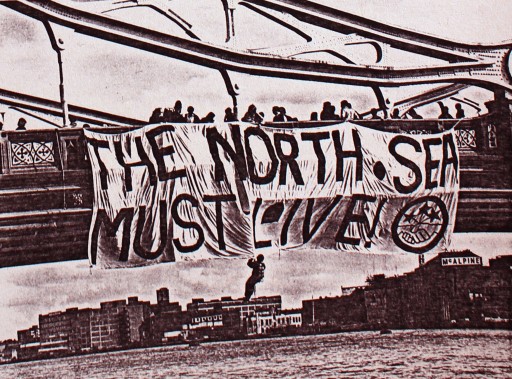

“The North Sea must live!” A singular event in the history of the movement. In 1987 at the NFI Congress in Brighton, a group of Naturefriends hangs a huge banner at the Thames Bridge.

[1] The Dutch, Belgian, Austrian, Alsatian and German Naturefriends received one house equipment for 50 to 60 persons each (information from Hans Welti given to the author).

[2] Activity Report (see reference 3) p. 4

[3] For the argumentation of the central committee see: activity report 1945. Zurich 1945, p. 3